Notes on Parallel Worlds

Scott Benzel & Norman Klein with Margo Bistis, John Hawk, and Patrick Vogel at Phase Gallery

Parallel Worlds: Scott Benzel & Norman Klein at Contemporary Art Library

Salomon saith, There is no new thing upon the earth. So that as Plato had an imagination, that all knowledge was but remembrance; so Salomon giveth his sentence, that all novelty is but oblivion.

–Francis Bacon: Essays, LVIII as quoted by Jorge Luis Borges in The Immortal (1947)

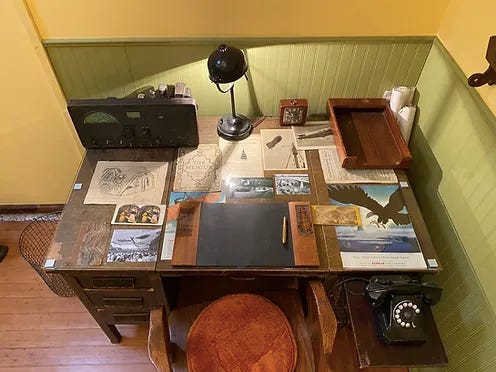

Entering the gallery one stumbles into Norman Klein and Patrick Vogel’s immersive installation The Secret Rise of Skunk Works, 2022, a simulation of a carefully-appointed movie set depicting the 1930’s Burbank garage-office of “Barney”, a faceless fixer laboring in the shadow of the ascendent military-industrial complex during the lead-up to World War II. Barney works for another man—Harry Brown (protagonist of Klein’s and Margo Bistis’s The Imaginary 20th Century)—monitoring communications “across the pond”. Vintage electronic equipment and low-level spy paraphenalia (a shortwave radio, a Soundscriber (used by spies for their audio reports), a clutch of maps) litter the small office, as does evidence of Barney’s chief hobbies–bird hunting and amateur taxidermy. The furnishings and objects are period artifacts selected by Klein and Vogel from the Warner Bros. Property Department (Upon completion of the installation, Klein remarked with satisfaction that the piece could be the set of a low-budget 1930’s film.)

From Klein’s accompanying text:

Inside this tiny office, Barney was hired to listen, to never send a message. On the day he was hired, his employer, Harry Brown showered him with faint praise. At their one and only meeting, Harry stared him down, and said: “I prefer agents who have a proven history of criminality. Nothing lethal but showing disrespect for the law. I want flexible morality, the ability to lie when needed. But to me, and let me repeat—to me-- they can never lie. To me, they are as loyal as a smart hunting dog.”

“I don’t want you to think you know the big picture. You cannot. You send no messages on your own. No typewriter in the room. Your job is to be the ears of a mission larger than history.”1

A period radio plays the popular music of the time. The tail-feathers of a taxidermied pheasant bridge the edge of the set with the gallery beyond it…

John Hawk’s film One-third of a dollar, 2024, based on an improvised story by Klein, loosely follows the story of Leon Theremin, inventor of the extraordinary musical instrument bearing his name (an object of fascination for Vladimir Lenin) and later, a master builder of espionage equipment for the Soviet state under Stalin, including a unique bugged medallion that would hang undetected for years in the U.S. embassy in Moscow.

In his story-telling, Klein sometimes paints outside the lines of established fact, linking, for example, Theremin to Harry Brown’s ancestors the Angewynnes. Klein’s possible worlds haunt the edges of official history, reveling in the seamless plausibility of a fabulation, or the narrative necessity of a retcon. Klein—in his story-telling as in his wunder-romans—moves history closer to the space of art, feathering the edges of both…

Per Borges:

“It may be that universal history is the history of a handful of metaphors.”

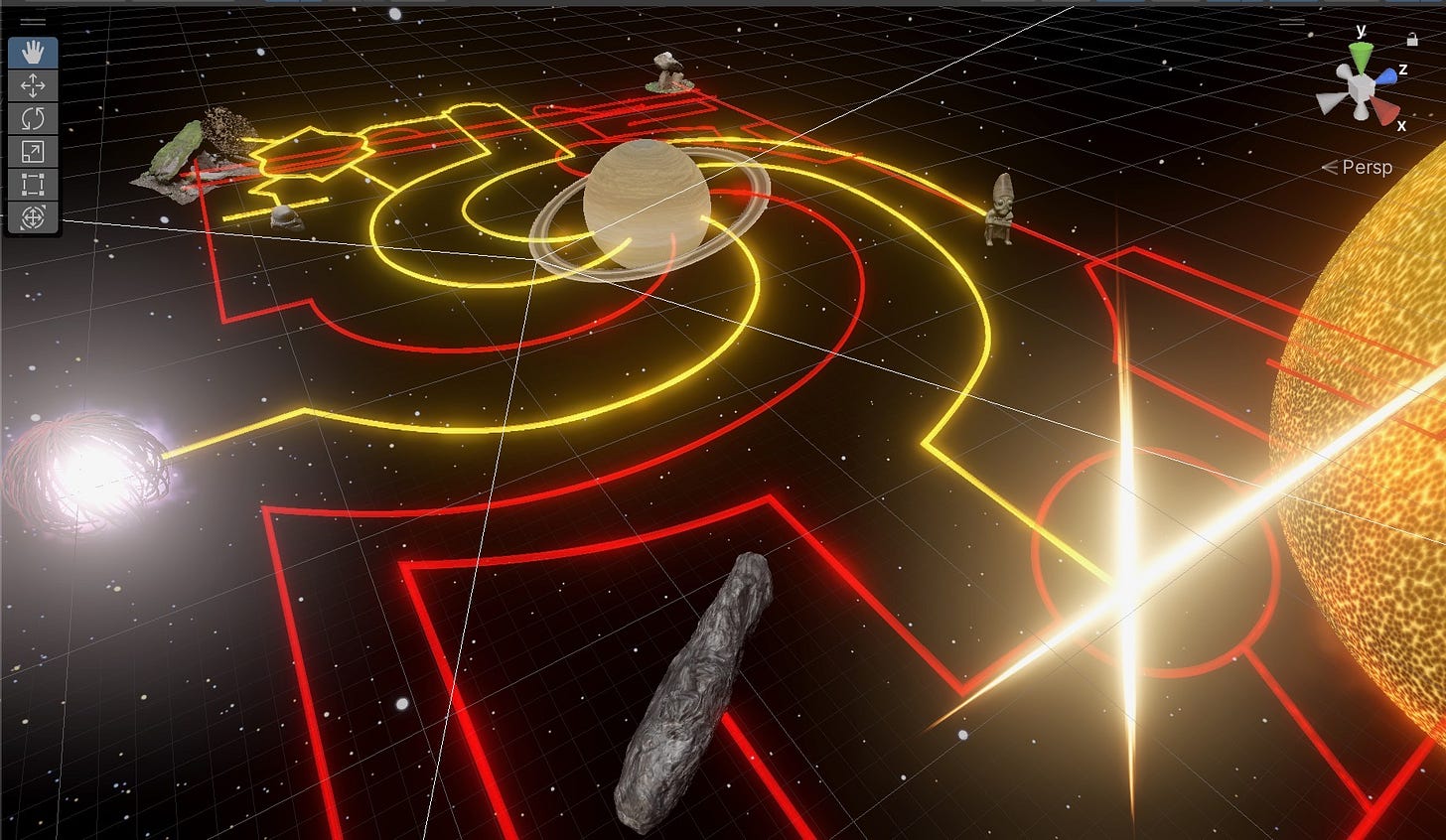

On the wall opposite Hawk’s film is a large flatscreen displaying I. FORGET THE LABYRINTH/IGNORE WHAT MANNER OF BEAST/MIGHT RANGE IN IT; II. ALL MEAN CLOSEQUARTERED THINGS/WHO SELF/DESTRUCT/YET SPARE A NUCLEUS TO BREED BACK, 2024, my “videogame” (programmed by Naomi Sam), its title derived from the channeled Ouija Board poetry of Sylvia Plath and James Merrill. Literary scholar Helen Sword addresses the poets’ use of the device in Ghostwriting Modernism:

In the second half of the twentieth century, a number of writers sought to provide a fresh twist on the ancient prophetic paradigm by foregrounding more explicitly than ever before the relationship between spirit mediumship and literary production. Poets Sylvia Plath and James Merrill…would move beyond the low cultural qualms of their high modernist forebears to explore the affinities and alliances between automatic writing—a mode of mediumship that affirms the special selection of its practitioners even while conveniently displacing the very act of authorship—and their own poetic creativity.2

The “game” itself is unique in a number of ways: it has only one controller—an accelerator pedal—no real obstacles, and no goal. One goes either fast or slow, moving steadily across land- and star-scapes through labyrinths of tubes filled with (digital) stage blood and honey. Scanned artifacts from museums around the world flicker past: plaster mathematical models, beehives, a 5th Century B.C.E. Minotaur bust. On the game’s second level (informed by the weird romantic-nuclear paranoia and (somehow airless) cosmic vision of the spirit channelled by James Merrill in The Changing Light at Sandover) the viewer (player?) drifts through data-derived simulations of cosmic and nuclear-physical phenomena, briefly traversing one of Saturn’s rings, glimpsing Oumuamau passing through whatever solar system this might be, glancing off a fission reaction, sliding across the stone of an ancient dolmen.

At the center of the gallery is a vitrine containing 31 objects from Carrie’s archive, 2024, assembled by Margo Bistis and Klein. “Belonging” to the fictional Carrie, Harry Brown’s niece and protagonist of Klein’s and Bistis’s wunder-roman/multimedia project The Imaginary 20th Century, the vitrine’s selection has been extracted from the evolving Roussellian wunderkammer maintained by Brown’s secretary Washovsky:

Along the main gallery inside, Washovsky hung a thousand pictures in four tiers. Against the walls, wooden legal cabinets were filled with more pictures—as well as news clippings and books. Large baskets held stacks of mostly unreadable, unpublished novels in manuscript (by Carrie’s suitors)—and finally acerbic diaries by Carrie herself, who could be darkly funny (particularly on icy days).

By the late twenties, Washovsky had automated all four tiers into a movable device. This machine delivered “episodes,” on something like a card catalog or an index. He did all this per Harry’s instructions. Upon metal hooks, he placed brass name cards. Above these were metal tags, labeling each drawer. For the top of each cabinet, he contracted workers at a dime museum to install optical devices, with magnifying peepholes. These cards flipped on a rolodex, to reveal thumbnail pictures, with captions that drove Carrie's story forward (or sideways). In turn, they could be driven or navigated by Harry. […]

The two men eventually curated fifty versions of Carrie’s life. From time to time, Carrie would look in as well.3

Symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum, 2024, looms across the wall to the left, its dimensions exactly those of the bus stop outside my Chinatown studio, its dual LED-lit frames displaying Duratrans blowups of trash collected on my walks between home (Elysian Heights) and studio. Behind it, a row of archival boxes contain more of the accumulation of detritus—a bag of “Doweedos” weed gummies ripped open from the bottom by impatient fiends; a torn-paper dashboard FUNERAL sign; dead aluminum shells from whipped-cream poppers; the elegant, gold, hexagram-infused packaging of “Double Happiness” cigarettes; a comically large transparent green pill bottle; a yellow-to-orange gradient vape pen; a rainbow-hued fake fingernail.

Beyond all of this lies a deceptively modest iMac portal to the massive, profusely illustrated interactive version of Klein and Bistis’s The Imaginary 20th Century (What if the riddle of The Imaginary 20th Century—“the future can only be told in reverse”-- is “as paradoxical as it is true,” as curator Hans Ulrich Obrist remarks in a review?4 ). Nearby, a monitor displays a video of Klein negotiating the sadly obsolesced interactive DVD-ROM version of his other major wunder-roman, Bleeding Through: Layers of Los Angeles, 1920-1986.

In his prescient 2007 essay Spaces Between: Travelling Through Bleeds, Apertures and Wormholes Inside the Database Novel, Klein writes:

In media (games, interfaces, electronics at home and outside – cellphones), the role of the reader has altered noticeably during this decade. So many new platforms have become comfortable to the public: blogs, wikis, my-spacing, u-tubing, iPods, and this week, iPhones.

After two corrosive generations of digital media altering our lives at home, codes even for what a story contains have noticeably shifted. At the heart of this change is home entertainment replacing what used to be called urban culture. The infrastructure for public culture in cities is vanishing rather quickly, particularly bookstores and live theater. That is simply a fact, not a gloomy prediction.

Museums have finally turned into cultural tourism, an extension of home entertainment. Pedestrian life in cities continues to be increasingly dominated by cultural tourism as well – by what I call scripted spaces (by scripted spaces, I mean staged environments where viewers can navigate through a “story” where they are the central characters. Thus, themed, scripted spaces can be on a city street, or inside a game, or at a casino).

This reconfiguring of the viewer has massive consequences. It has altered our national politics so thoroughly that our republic has, at last, outgrown the “vision of the Founding Fathers”. As I often say, half joking, the Enlightenment (1750–1960) has finally ended – quietly, under the radar, like lost mail.5

Outside the gallery in the asphalt-paved courtyard, on certain nights, my Negative SETI, 2024, beams sequences of code (programmed by Alan S. Tofighi) from retired studio worklights into the night sky. On the night of the work’s installation, a lone raccoon (of the non-fluorescent, non-talking variety6 ) sat mesmorized by the piece, not letting it leave its sight.

Physicists Hugh Everett and John Wheeler, with their Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics 7 , suggest that uncountable Parallel Worlds shadow our own: at each moment of decision, at every site of divergence, happenstance, or accident, possible worlds spin off, ghosting, onionskinning, and otherwise shading our world with undreamt-of folds of contingency.

Per Klein of his protagonist Harry Brown:

'“He worked at being a face you could easily forget. And he knew how to build imaginary events, in the newspaper especially. To summarize his ethics, he often liked to say. “lucky for me, fictions are more believable than facts.””

Parallel Worlds, on view November 2-December 7 at Phase Gallery, Los Angeles

From Norman Klein, The Secret Rise of Skunkworks: In Los Angeles, back channels were hastily set up in the spring of 1938. They were paid for mostly by the oligarchs who ran the city, and some by the mayor’s office (easily the most corrupt mayor in the US), some by the governor of California who hated Los Angeles. And these back channels were extensive: everywhere and throughout the west-- and Mexico, where agent provocateurs had been hired by Harry since the Mexican Revolution and civil war. This was multi-dimensional freebooting contract espionage. One had to keep many lids closed at once, and others open at the same time; while allowing tons of vital scientific and military data to pass safely across a distribution network ten thousand miles long.

For Los Angeles, there was one person usually put in charge of such back channels, when they were this massive. He was known by his assumed, false name, Harry Brown. He was a lawyer by trade, who kept a perversely low profile-- almost an agoraphobic. Since 1898, as a very young man, he had been erasing crimes embarrassing to the oligarchs of Los Angeles.

Harry Brown stayed mostly on an estate toward the eastern edge of the LA basin. He also had agents in Mexico, even Latin America, because he had worked secretly with the Marines on special missions since 1905. Harry famously (at least to the FBI) had something to do with the American entry into the First World War. He worked at being a face you could easily forget. And he knew how to build imaginary events, in the newspaper especially. To summarize his ethics, he often liked to say. “lucky for me, fictions are more believable than facts.” from Norman M. Klein, The Secret Rise of Skunkworks, Burbank: Office Space Gallery, 2022.

From Helen Sword, Ghostwriting Modernism: A deceptively simple device, a Ouija board consists of a flat piece of cardboard or paper inscribed with the letters of the alphabet (usuallyarranged in a circle or arc), the numbers from 0 to 9, and a few other common words and symbols such as YES, NO,a nd "&." Although it can, in theory, be employed by a solitary sitter, the board is usually operated by two or more persons who place their hands lightly on a small three-legged pointer or any other fairly mobile object (Merrill used an overturned teacup, Plath a wineglass). As the pointer glides from letter to letter without the conscious will or direction of its manipulators, one of the sitters uses a free hand to write down the board's messages, which are spelled out without punctuation marks or word breaks and can arrive, especially for experienced sitters, with breathtaking speed. […]

Both Plath and Merrill composed major works—Plath's "Dialogue over a Ouija Board" (written in 1957 but first published in 1981) and Merrill's The Changing Light at Sandover (published in four installments from 1976 to 1982)—that recount and reenact their respective experiments, undertaken roughly contemporaneously beginning in the 1950s, with the form of automatic writing known as the Ouija board. Plath's eleven-page "Dialogue" documents a single session with the board, whereas Merrill's monumental Sandover trilogy spans 560 pages and nearly three decades. […]

Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and Henri Bergson, three of the modernist era's most influential intellectual avatars, were corresponding members of the London Society for Psychical Research who wrote or lectured on the origins and effects of mankind's persistent belief in spirit survival. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Mina Loy, seemingly unlikely acolytes of the other world, all attended seances during or just after the war years. And even confirmed skeptics such as Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf, while shunning spiritualist practice, routinely filled their fiction, poetry, and essays with mediums, ghosts, seances, disembodied voices, and other invocations of the living dead. from Helen Sword, Ghostwriting Modernism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Norman M. Klein and Margo Bistis, The Imaginary 20th Century. Karlsruhe: ZKM, 2016.

https://ccs.ucsb.edu/news/2018/future-can-only-be-told-reverse

Norman M. Klein, Spaces Between: Travelling Through Bleeds, Apertures and Wormholes Inside the Database Novel from Jens Martin Gurr (ed.), Norman M. Klein's “Bleeding Through: Layers of Los Angeles” An Updated Edition 20 Years Later. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2023

“It may be surprising to learn that the credited inventor of the most important workhorse in molecular biology—the polymerase chain reaction or PCR—once claimed he had seen a talking fluorescent raccoon near his cabin, which may or may not have been an alien.” from The Man Who Photocopied DNA and Also Saw a Talking Fluorescent Raccoon: Kary Mullis shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 for his discovery of an elegant technique to amplify parts of the DNA molecule, an invention that changed the face of medical diagnostics and crime scene investigations. https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/technology-history/man-who-photocopied-dna-and-also-saw-talking-fluorescent-raccoon

Everett, Hugh; Wheeler, J. A.; DeWitt, B. S.; Cooper, L. N.; Van Vechten, D.; Graham, N. (1973). DeWitt, Bryce; Graham, R. Neill (eds.). The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton Series in Physics. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.